2

In order to prepare its graduates for their professional lives in and around mines, UC Berkeley’s College of Mining could not just rely on teaching theory. The students had to learn how to lay out and construct a mine, how to blast their way into rocks, how to shore up the hollows they created. Perhaps most importantly they had to learn how to adapt to hours of hard work underground in dark, wet and poorly ventilated conditions. Hence in 1916 Frank Probert, a newly appointed Professor of Mining, started his students in digging a demonstration and teaching mine on campus. He did not have to venture far from the Hearst Memorial Mining Building, because the foot of the Berkeley Hills lies just a few a dozen feet to the east. The mine entrance – where you are standing now – is right across from the northeastern door of the building.

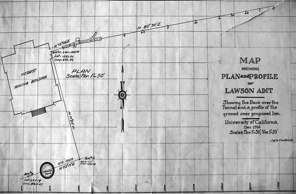

Over the years, classes of the students dug a 200 ft long horizontal adit eastward into the hills to provide “sound, practical training in drilling, drifting, blasting, timbering, and mine surveying” as the classes were advertised in the catalogue.

Students also had to become familiar with the technical language miners use. The word “adit” describes a horizontal passage leading into a mine – in contrast to a “shaft”, which is a vertical passage. Adit is also different from a “tunnel”, which has both an entrance and an exit. The adit here was named after Andrew Lawson, a Berkeley geologist who lead the team of eminent scientists studying the aftermath of the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. Starting in 1914 Lawson was also the Dean of the College of Mining for four years.

In the late 1930’s when new campus buildings were planned east of Gayley Road, questions were raised about the stability of the slopes – after all, the Hayward Fault was only a few yards away from the proposed building sites. In order to investigate the geologic conditions, UC Berkeley geologist George Louderback had the adit extended by 700 ft until it reached the Hayward Fault. He was surprised by what he found:

– near what is now Stern Hall and Foothill Student Housing the fault was split into at least two branches,

– the traces were defined by a peculiar mix of serpentine and metamorphic rocks.

He also discovered several accumulations of rounded cobbles similar to those found in Strawberry Canyon further to the southeast. Louderback interpreted these as exposures of the offset of Strawberry Creek, indicating a displacement of more than 600 ft north along the Hayward Fault (see also section 5).

After Louderback’s extension, the adit was eventually abandoned. Today much of it has collapsed and it is deemed unsafe to enter the mine. However, the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory (BSL) has plans to place a seismic monitoring station into the adit.

Walk back to the Mining Circle and take a very sharp, almost 180 degree turn to the left. Then walk across the parking lot of Donner Laboratory until you reach a stairway. Climb the stairs to the top and turn left. After about 20 yds, Founders’ Rock is on your right.